Since the birth of civilisation, language has been one of humanity’s greatest tools. Developing alongside human society, language has become more than simple communication and education, having the power to shape perspectives and attitudes towards the subject at hand.

As early as the 18th century, when shipbuilding and mining were consuming increasing amounts of wood [1], people in Europe have been conscious about resource sustainability. Then, in 1975, US scientist Wallace Broecker brought the term ‘global warming’ into the public’s consciousness after including it in the title of one of his papers [2]. Public awareness of the issues around sustainability and climate change has existed for decades, even centuries, but has never been as widespread as it is today. This growing recognition can be explored by taking a deeper look at how the language of climate change has evolved and the importance that this has.

Talking About Climate Change

The concepts of climate change and global warming originated with the scientific community. Consequently, important evidence-based information is often communicated to the general public in scientific and technical language that hinders accessibility and understanding. The recent talk of the town of keeping global warming to less than 2 degrees Celsius by 2100, for example, bears little meaning unless it is put in context. This temperature increase could cause more than 90% of global coastlines to experience a 20cm sea level rise, increasing coastal flooding and reducing a third of per capita crop production in Southeast Asia, it could cause the annual reoccurrence of the 2015 heatwave in India and Pakistan, which killed nearly 1700 people in two of India’s worst-hit states alone [3], and it has the potential to kill all coral reefs [4]. That being said, many of these extreme events have not yet been experienced, and their future consequences can only be conjured by our imagination.

The effects of global warming are often discussed to be materialising decades into the future. Such language reinforces the distinction between our present selves and our future selves. This separation is problematic, as studies have found that we experience difficulties forming bonds with our future selves. In fact, we have as much connection with our future selves as we do with a stranger that we pass by [5]. This future-based discussion of climate change consequently fortifies the idea that climate change is somebody else’s problem, even though our actions now will directly impact and shape the world we will be living in in the future.

Another problematic observation of how we use language is the creation of a false dichotomy between us and nature. Phrases like ‘impact on the environment’ create the distinction that the environment is separate from us, whereas the phrase ‘impact on our environment’ emphasises that we exist as a part of it [6]. This language use cumulates in the concerning situation where climate change becomes out of sight, out of mind.

What is more, there seems to be active underreporting with regards to climate change by some news outlets. A report on American media, for example, found that an entire year of climate news coverage was lower than what was received by the British royal baby Archie in a single week [7].

Figure 1: Word cloud of the commonly used words related to climate change in the Guardian from 2017 to 2020. Data obtained from The GDELT Project.

Taking A Closer Look: Climate Change In The Eyes Of Oil And Gas Companies

Oil and gas companies have been among the most vigorous opponents of climate related policies, with expenditure on climate lobbying reaching up to $53 million a year [8]. This defensive stance against climate change mitigation carries through in their annual reporting. An analysis of the corporate social responsibility and environmental reports from 2000 to 2013 highlights a few linguistic techniques oil and gas giants use to deflect having to take actions to mitigate climate change.

Preference for ‘climate change’ as opposed to ‘global warming’

‘Climate change’, while being a more scientifically comprehensive description [9], is a neutral term, whereas ‘global warming’ implies a direct consequence – the warming of the planet. Furthermore, the Oxford English Dictionary definition for ‘global warming’ assigns human activity as the cause, while human agency is omitted from the definition for ‘climate change’.

Downplaying the strength of scientific evidence

While scientists often use uncertainty estimates to convey their confidence levels in the accuracy of their data, companies can misconstrue this uncertainty, turning it into scepticism of the evidence presented. In phrases such as ‘the risk of eventual climate change caused by anthropogenic emission’, the use of the hedge ‘eventual’ also serves to decrease the causal relationship between emissions and climate change.

Magnifying the importance of meeting energy demand

Although companies acknowledge the importance of managing emissions, they often introduce growing energy demand as a factor of equal importance, as ‘meeting the enormous energy demand growth and managing the risk of GHG emissions are the twin challenges of our time.’ This then construes that companies need to balance climate change mitigation efforts with their need to meet increasing energy demand, which is a favourable strategy for the oil and gas industry.

Relocating responsibility

By including other stakeholders such as governments and consumers when addressing climate mitigation, companies shift the responsibility away from themselves towards a shared accountability with other societal actors. This downplays companies’ responsibility to change their behaviour or even lead the change.

Nevertheless, a more recent analysis of the reports of three energy companies highlights that these companies have acknowledged that climate change poses a business risk. One company has even embraced it as a business opportunity, hinting at a positive shift in how the energy industry views climate change [10].

Putting Climate Change At The Forefront Again

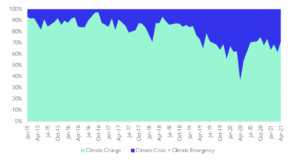

Figure 2: Use of the phrase ‘Climate Change’ compared to ‘Climate Crisis’ and ‘Climate Emergency’ from January 2015 to April 2021 in the UK parliament. Data obtained from Hansard.

As the years pass, the negative consequences of climate change become ever more apparent. The need for us to adapt our behaviour to prevent fur ther environmental damage has been stated time and time again through protests and individual activists such as Extinction Rebellion and Greta Thunberg. The media has also taken considerable steps to change how they repor t on climate change issues, a move that has significant effects given the media’s wide reach.

In 2019, the Guardian made a climate pledge to make six changes to the language used in their reporting. These include the rebranding of ‘climate change’ to ‘climate emergency’ or ‘climate crisis’ to reflect the urgency with which we need to take action as well as replacing ‘climate sceptic’ with ‘climate science denier’ to emphasise the robustness of scientific evidence [11]. A study of US news media content also revealed a positive shift in the language used in regards to climate change reporting. Research has found that there has been a decline in framing climate change as economically costly as well as a sharp decrease in communicating the uncertainties associated with climate science, both of which reduce an individual’s inclination to support and engage in climate action [12]. In contrast, language conducive to climate action engagement has been on the rise. These include emphasising the economic benefits of climate action and communicating climate risk in the present tense. As American feminist writer, Rita Mae Brown says, ‘language exerts hidden power, like the moon on the tides.’ Let us be mindful of and actively use this power to make a positive change in our environment.

Bibliography

[1] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/15693430600688831

[2] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-15874560

[3] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-32926172

[4] https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/chapter-3/

[5] https://www.livemint.com/Opinion/Mm8Q1TpcSRFUptKODSUd3H/Our-future-selves-arestrangers-to-us.html

[6] https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/granthaminstitute/public/publications/briefing-papers/Towards-a-unifying-narrative-for-climate-changeGrantham-BP18.pdf

[7] https://www.mediamatters.org/abc/abc-news-spent-more-time-royal-baby-one-weekclimate-crisis-one-year

[8] https://www.forbes.com/sites/niallmccarthy/2019/03/25/oil-and-gas-giants-spend-millionslobbying-to-block-climate-change-policies-infographic/

[9] https://www.preventionweb.net/files/2276_climatechangefinal.pdf

[10] https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/CCIJ-08-2018-0088/full/html

[11] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/may/17/why-the-guardian-is-changingthe-language-it-uses-about-the-environment

[12] https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2019.00006/full